|

SOURDOUGH PIZZA On pizza nights, rules fly out the window. Any shape, any sauce, any toppings are possible, without the need to compromise. You don’t like pineapple on your pizza? Then make your own. I have struggled to settle on my optimal pizza recipe over the years. Recipe after recipe, formula after formula, they always ended up too slack, too stiff, too sour, not sour enough, too tough, too chewy, too delicate, or too plain ole finicky. Plus, the best recipe for a sizzling hot pizza oven is very different from the best recipe for a home oven, even with the best stones, steels, and peels at your disposal. This, my *ahem* pizza de resistance, came from a few months of recipe testing and crucial knowledge from Andrew Janjigian, who dedicated all of November to sharing his pizza tips in his phenomenal newsletter. The recipe is exceedingly flexible and utilitarian—while I wouldn’t use it for deep-dish (but why would you make deep-dish?), it could be used for just about any other pizza style you’re craving. PRE-RECIPE NOTE The pizza dough should be prepared and refrigerated at least a day before baking. You can let it chill in the fridge for up to 5 days before stretching, topping, and baking, but note that the sourness and slackness of the dough will increase with time. I’ve found 1 to 2 days to be the sweet spot. This recipe also assumes you are using a strong, active sourdough starter at 100% hydration to seed the levain. If your starter has been in the fridge for a week, add at least a day to the recipe timing below to allow for 2-3 feedings (spaced 8 hours apart) before mixing your levain. If it has been in your fridge for longer than a week, add at least two days to the recipe timing to give it enough time to return to full strength. And finally, fermentation fluctuates with temperature. These instructions work best if your kitchen ranges from 68-72 degrees F. If your house runs a little warmer, use cooler water and/or store your flour in the freezer. If your thermostat registers a bit cooler, use warmer water (never hot) or try storing your levain and dough in the oven with the light on while it's fermenting. TOTAL TIME: 1.5 days ACTIVE TIME: 1.5 hours INACTIVE TIME: 35.5 hours ACTIVE LEVAIN MIX TIME: 15 minutes INACTIVE LEVAIN FERMENTATION TIME: 6-8 hours ACTIVE FINAL DOUGH MIX & FOLD TIME: 30 minutes INACTIVE FINAL DOUGH FERMENTATION TIME: 4 hours ACTIVE FINAL DOUGH SHAPING TIME: 15 minutes INACTIVE FRIDGE FERMENTATION TIME: 24 - 120 hours (1 - 5 days) INACTIVE ROOM TEMP. REST & OVEN PREHEATING TIME: 1 hour ACTIVE SHAPING, TOPPING, & BAKING TIME: 30 minutes

*If you prefer less wheat for a lighter texture, you can decrease the whole wheat flour to 80g, increase the AP flour to 400g, and decrease the water to 250g in the final dough recipe. MIXING 1. About 6 to 8 hours before you plan to mix your pizza dough, build your levain by mixing 20g of sourdough starter with 60g of room temperature water, 30g AP flour, and 30g wheat flour in a container large enough to allow it to expand three times over. Cover and leave to ferment at room temperature. 2. When your levain has more than doubled in size and has a subtly domed surface with shiny, protruding bubbles, it’s ready for mixing. 3. Take 115g of your levain and mix with 270g room temperature water and 20g olive oil. Add 11g salt and 240g each of all-purpose flour and whole wheat flour, mixing until combined and homogeneous. I prefer to use my hands, but you may also use a spatula or the low speed of a mixer with a bread hook. If the dough feels too tough or dry, add water in tbsp increments until the dough comes together and feels pliable.

7. Repeat for the other pizza and enjoy the fruits of your labor!

0 Comments

EVERYDAY SOURDOUGH RECIPE

Having a staple sourdough is a wonderful joy. After making this bread over and over again, tweaking the hydration and the flour types slightly along the way, I have grown to love this loaf more through repetition. While I wouldn't call it predictable, as sourdough changes with the seasons, baking hundreds of batches of this bread does give me a consistently delicious loaf. This is the bread I recommend for your daily tables: It's versatile, classic, and dependable. This recipe features a meld of local bread flour, all-purpose flour, local whole rye flour, and local whole wheat flour, but it can be adapted to suit your pantry. If you're looking to acquire some great local grains, I have recommendations for local farms and mills in the mid-Atlantic region included in the recipe below. You can also check out the growing directories here and here to find a source closer to home. This recipe yields 2-1kg loaves (approximately).

EVERYDAY SOURDOUGH: TOTAL DOUGH FORMULA

EVERYDAY SOURDOUGH PROCESS

Prep

Proof

If you give the recipe a try, I'd love to hear how it goes! Let me know in the comments or on Instagram by tagging @jennycstarrs or using #starrssourdough! SOURDOUGH FOCACCIA RECIPE This is such a simple, forgiving, and adaptable recipe that I very nearly brushed off writing it up. Focaccia is a pleasure for me to make because of its versatility and variability. Savory or sweet; two-day fermented or same-day baked; in a round or spread out in a pan; it's going to be delicious just about any way. I'll note the plentiful options and side-routes you can take in the process along the way! This recipe yields one full pan (approx. 9 x 13 in) of focaccia or two rounds (approx. 10 in diameter) of focaccia, and can be topped with just about anything you desire. Tip: Make sure your toppings are sliced thinly, or else they can weigh down the focaccia and lead to soggy pockets. My current favorites include coarse sea salt, garlic, and rosemary; cherry tomatoes and basil; peaches, herbes de Provence, and goat cheese; and pesto and nuts.

SOURDOUGH FOCACCIA: TOTAL FORMULA BAKERS PERCENTAGES

SOURDOUGH FOCACCIA PROCESS

Mix

Final rise

Bake

TOMATO BASIL SOURDOUGH RECIPE This naturally leavened, red-tinged loaf is the epitome of summer. Whole rye gives it a denser crumb and a delicious tang to bring out the acidity of the tomatoes and the freshness of the basil. And paprika gives it a flavorful zing and deepens its natural color. Pair this loaf with some bruschetta or a Caprese salad or even just olive oil and herbs, and you're in for the perfect summer meal. Recipe yields 2 1-kg loaves. TOMATO BASIL SOURDOUGH BAKER'S PERCENTAGES (a universal, slightly more technical way to share recipes that is explained here, but you can also just ignore this)

TOMATO BASIL SOURDOUGH PROCESS

Mix

SOURDOUGH BANANA MUFFIN RECIPE

The two constants in my kitchen are overripe bananas and excess sourdough starter. I prefer banana muffins to their denser companion, banana bread, which I always struggle to cook through. Plus, these are easy to freeze and then thaw individually when you need a sweet treat for breakfast! Recipe yields 12 muffins. MUFFIN INGREDIENTS

STREUSEL INGREDIENTS

For a dairy-free alternative, replace the butter and sour cream with vegetable oil, and use 1/2 cup honey in the streusel instead of the butter and brown sugar. SOURDOUGH BANANA MUFFIN PROCESS

OLIVE AND HERB SOURDOUGH RECIPE

This olive and herb sourdough is packed with salty, herby flavor, plus a subtle nuttiness from whole spelt flour. It even entranced me, a firm olive hater. I'm still far from an olive advocate, but after baking this bread for my olive-loving partner for a few years now, I finally see the merits of this briney fruit. LEVAIN

FINAL DOUGH

OLIVE AND HERB SOURDOUGH BAKER'S PERCENTAGES (a universal, slightly more technical way to share recipes that is well explained here, but you can also just ignore this) LEVAIN 100 percent hydration 50 percent rye 50 percent bread flour 25 percent ripe starter (aka 1:4 ratio) TOTAL DOUGH FORMULA 73 percent hydration (15 percent pre-fermented in levain) 67.5 percent bread flour (7.5 percent pre-fermented in levain) 25 percent spelt flour 25 percent olives 7.5 percent rye flour (pre-fermented in levain) 2 percent herbes de Provence 1.5 percent salt EQUIPMENT

OLIVE AND HERB SOURDOUGH PROCESS MIXING Evening

Morning

BAKING

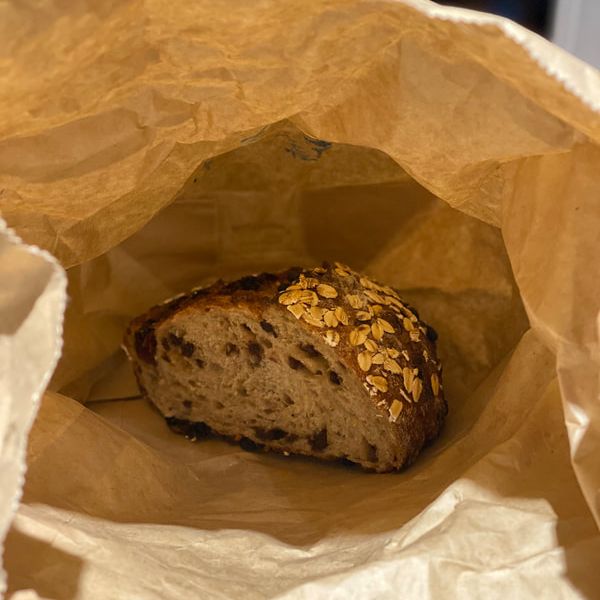

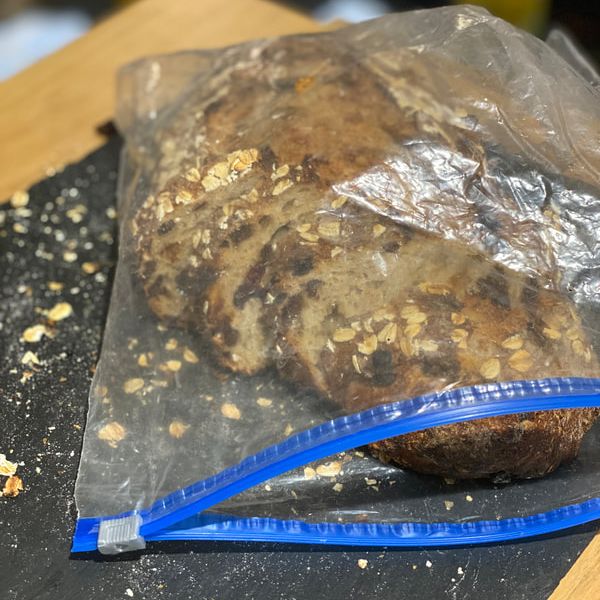

BEGINNER SOURDOUGH RECIPE This is a flexible sourdough recipe for beginning bakers. Feel free to change things around to fit your schedule, pantry, and tastes. You can put your dough in the fridge directly after the bulk fermentation step and shape it later, or bake it directly after shaping and proofing instead of giving it a cold fridge rest. You can substitute all all-purpose flour instead of a portion of whole wheat, or use a meld of grains, like einkorn, spelt, or rye, for the 140 grams of whole wheat that the recipe calls for. Most importantly, get up to your elbows in the dough and feel the magic of sourdough. Levain -20 grams active starter -80 grams water -80 grams bread or all purpose flour (unbleached) Final Dough -180 grams levain -235 grams water -235 grams bread or all purpose flour (unbleached) -140 grams wheat flour (or all purpose if that's all you have on hand) -9 grams salt PROCESS SAMPLE WEEKEND BAKING TIMETABLE -Thursday evening (between 8 and 10 p.m. - flexible): Take your starter out of the fridge, discard and feed it (keep 30-50 grams of starter and then mix in the same amount of flour and water). Leave the starter at room temperature. -Friday morning (between 8 and 10 a.m. - flexible): About 8 to 12 hours hours after your morning feeding, repeat the same discard and feeding process. -Friday evening (between 8 and 10 p.m. - flexible): About 8 to 12 hours hours after your evening feeding, mix your levain. Weigh out 80g of water (no need to be finicky - I use a 5g range) in a separate, mid-sized bowl. Remove 25g of mature starter from your main starter (it should be bubbly and sour-smelling), and put it in the 80g of water. It should float to the top or near the top. Break up the starter in the water, and then add in 80g of all purpose or bread flour. Mix well and leave at room temperature. You can store your remaining starter back in the fridge without feeding again. -Saturday morning (9 a.m.): In a wide bowl (or in a mixer's bowl if you have both a mixer and a dough hook), weigh out 235g of water. Your levain should have some nice air bubbles, doubled in size, and pass the float test. Scrape your levain into the bowl and break it up in the water. Weigh out your flour, using either 235g of all purpose/bread flour and 140g of wheat flour or simply 375g of all purpose/bread flour, and add to the bowl. Then weigh and add 9g of salt and mix together thoroughly, until all the flour is hydrated. You can perform a series of "slap and folds" in the bowl to give the dough some initial strength, but don't worry too much about kneading. Bulk fermentation (9:15 a.m. to 1:15 p.m.): Perform a series of folds in your bowl by grabbing the underside of the dough, stretching it out one way (but not allowing it to tear), and folding it over on itself. Rotate the bowl and do this in each direction for a total of four folds. Cover the bowl with a kitchen towel and leave it for 1 hour, and repeat the folds every hour, so at 9:15, 10:15, and 11:15, for a total of four sets of folds. You can set a timer to remind you, but, again, don't be too finicky. 5, 10, even 15 minutes early or late is fine. During the folds, the dough should transform from a shaggy and sticky mound to an extensible, smooth ball. If it still feels hard to handle at 11:15, add in an extra set of folds at 11:45 and/or double up on your folds, doing two folds in each direction for a total of eight folds. You can also do this if you forget a fold. But it is important to give your dough a rest from folding for the final hour, from 12:15 to 1:15, so that it's relaxed when you go to shape it. 1:15 p.m.: Plop your dough onto a lightly floured countertop. Pick up the edges and make sure they're not sticking to the counter - if so, remove the stuck bits and reflour. Gently press down on the dough, but not so hard that you completely de-gas it. Stretch out a corner of the dough and fold it into the center. Repeat with each corner, until you have a little package of dough. Flip it over and let it rest for 15 minutes. This is called the "preshape." 1:30 p.m.: Return to your preshape for final shaping. Turn the dough over, so that the smooth, floured side is again facing down. Fold the corners in again, and flip the dough over again so that the sealed ends are on the bottom and the smooth side is on the top. With your hands cupping under the farside of the dough, pull the ball back toward you, creating surface tension on the boule. Rotate the dough and repeat until the dough is taut, but not going so far that it tears. If you have a banneton, lightly flour it and place the dough into it with the smooth side facing down. If you do not, then put a sheet of parchment paper into a medium sized bowl and lightly flour it, making sure that you have extra parchment sticking up on the sides of the bowl (this will make the transfer for baking easier!). Place the dough into the parchment-lined bowl with the smooth side facing up. Let rest and rise on the counter for 30 minutes, then store in the fridge for the night. Sunday (noon): Time to bake! I usually wait until the evening, to give it a longer time in the fridge, but you could speed it up to bake in the morning if needed. Preheat your oven to 475 for 30 minutes. After 30 minutes, place an oven safe pot, Dutch oven, or combo cooker in the oven to preheat for the final 30 minutes, with the lid on. If you don’t have a sufficient oven safe receptacle, you can put a pot of water on to boil and place a cast iron pan or other high-heat stable pan (not glass) on the bottom rack of your oven. Remove your dough from the fridge and your Dutch oven from the oven. Take off the lid and, if you have a banneton, turn it over to let the bread slide out onto the bottom of the pot. Score the top of the loaf with a quick, decisive slash, using either a sharp knife or a razor blade. If you don’t have a banneton, score your bread and then, wearing oven mitts, grasp the sides of the parchment paper with your dough on it and transfer it into your pot. Place the lid on and put it in the oven. Without a pot, simply place your scored bread on a baking sheet (with parchment or silicon under it so that it doesn’t stick) and put it in the oven on the second rack. Pour the boiling water into the cast iron pan to create steam. Bake for 20 minutes, and then either remove the lid of your pot or remove the steam-making pan. Bake for 10 minutes, rotate the loaf 180 degrees, and then bake for 10 to 15 more minutes, until the crust is golden and the bottom sounds hollow when tapped. If you have a thermometer, the bread should have a temperature of 200. Remove the bread from the pot to cool, waiting at least two hours before slicing! Part of sourdough's magic is its shelf stability and long-last freshness after it's pulled from the oven. So once you've baked or bought a loaf of sourdough, you can maximize its freshness with these storage techniques. Up to 2 days: On the counter.

Up to 5 days: Under a bowl

Up to 5 days: In a bag or breadbox Paper or cloth bags are more breathable alternatives to plastic. You could even wrap your bread in foil, a tea towel, or beeswax wraps. And while plastic bags aren't usually a good way to store your bread, they may come in handy in certain drier climates, where you need to retain as much moisture as you can. But in D.C., and especially during D.C. summers, plastic often traps too much humidity. Bread boxes can be very handy if you're an everyday bread eater with plenty of counter space. They come in endless different sizes and materials, and can store multiple whole or half loaves. Up to 3 months: In the freezer

Bread storage don'ts

Saving stale bread

There will come a day when, despite your best efforts, you leave a loaf out too long. But there are still many alternatives to the garbage bin or the compost heap. Bread crumbs, garlic bread, croutons, crisps, French toast, and bread pudding are all excellent projects for stale sourdough. This guide will walk you through maintaining an established sourdough starter. This is handy for folks who want to start baking with sourdough, but aren't ready to coax their own starter to life. You can get a sourdough starter by asking a fellow baker or bakery to share their starter, which is also referred to as a sourdough, mother, or levain. I'm always happy to disperse some of my four-year-old starter to folks in D.C. - leave a comment or send me a note and I'll get you some! Sourdough is a living culture, similar to Greek yogurt, cultured butter, kombucha, and other fermented products. It’s an intertwined ecosystem of lactic acid bacteria, called lactobacilli, and different strains of wild yeast, and it's maintained with the proper balance of flour, water, air, and time. The lactobacilli breaks down flour and water into starches and sugars while creating an acidic environment that wards off other bacteria and gives the starter its sour tang. The wild yeast feasts on the sugars and produces carbon dioxide as a byproduct, creating the bubbles and rise in the starter. To encourage that natural process, you need to keep your starter cozy, balanced, and fed in order for it to be stable and active for your baking projects. There are many different ways to create a sourdough starter, and I'll be creating a guide for that soon, too. One of the most intriguing methods I learned about is from Ruth Allman's "Alaska Sourdough," which suggests leaving a pot of potato water, flour, and sugar out until it starts bubbling, while counseling Alaskan frontiersmen to watch their thermometer closely. I created mine in 2016 following the simplest method: air, flour, water, and time. And that’s all your starter needs to stay happy, too. FEEDING YOUR STARTER One of the most important steps to keep your starter healthy is knowing when it's ready to be refreshed or fed. A few visual clues are if you can see air pockets through the side of the container, if there are elevated, glistening bubbles on the surface of the mixture, and if its volume has doubled from its original size. Scent-wise, your starter should smell ripe, with a vinegary, yeasty, tangy, fruity aroma. If the bubbles are small, the volume of the mixture has receded, or it smells alcoholic, your starter is over-fermented and definitely needs to be fed. This happens when the lactobacilli and wild yeast in your starter have consumed all the flour and water available. The lactobacilli starts to get overly acidic and sour, overwhelming the yeast with too much lactic acid and stopping the production of carbon dioxide. Baking with an over-fermented starter or levain will contribute to a stronger sour taste and diminish your bread's rise. I maintain my sourdough starter at 100 percent hydration, which means it's kept at a ratio of 1 part flour to 1 part water. The reason that's considered 100 percent hydration is because bakers percentages are determined by a formula's flour weight. Here, the water is 100 percent of the flour weight. Thus, 100 percent hydration starter. If I've given you a sourdough starter, it contains approximately 50 grams of mother starter. To feed or refresh any size starter:

Weighing bread baking ingredients is much more precise than measuring their volume; however, if you don’t have a scale or don’t want one, you can look up rough conversions from grams to cups and use that approximate estimate. 50g of water is about 1/4 cup, and 50g of flour is about 1/3 cup. Your starter’s activity is greatly influenced by temperature. If your culture is stored in a chillier spot, its metabolism will slow down, taking longer to reach peak fermentation than if it's in a warm location. Use this knowledge to aid your baking process. If you want to speed up its activity, put it near your stove or heater. If you want to slow it down, store it near a drafty window. Just don’t heat it above 110 degrees Fahrenheit, as that will kill off the yeast. After feeding your starter, loosely secure the lid of its container or cover it with a tea towel in order to allow the carbon dioxide to escape. The culture will start to froth, bubble and expand, letting out gas along the way. It can take anywhere from 5 to 12 hours for the starter to hit its peak — a good rule of thumb is about 8 hours — and then it will begin to recede. To feed you sourdough starter a second time without building up its mass:

The removed sourdough, which is often called “discard", can be thrown away, used, or saved in your fridge and substituted in to your favorite recipes in place of equal parts flour and water. Some of my favorite uses for discard are Greek yogurt flatbreads, muffins, crackers and pancakes.

BAKING WITH YOUR STARTER You want to use your sourdough starter at its most active, bubbly level when you're baking, so that means you have to plan ahead. It can take a few feedings to make sure your culture is awake and moving, especially if you store it in the fridge (more on that below). A reliable way to check that your sourdough is primed before you start baking is by using the float test. When you think your starter is at its peak activity level, break off a small piece and drop it into a cup or bowl of water. If it floats, that means it’s ready to use. If your recipe calls for more than 100g of sourdough starter, then you’ll want to “build” up your starter before you plan to start baking. To do this, you can skip the discard step when feeding your starter, or remove less than 2/3 of its weight before replenishing it in order to make sure you have the right amount of starter before you start baking. And make sure you always have a buffer so that when you're mixing your sourdough starter into your full recipe, you have some left over to keep your starter going. And some recipes call for a “levain” or “pre-ferment,” which means creating a different mixture of grains and water (and sometimes other ingredients too) with your sourdough starter before baking, rather than using your 100 percent hydration sourdough starter. If so, make sure to save a portion of your original starter in a separate container so that it can live on in its original form. STORAGE Not ready to bake with your sourdough starter? Make sure the container is covered tightly with a lid and place it in your refrigerator. This will slow down its fermentation to a sluggish pace, letting you take a break from feeding it while you’re not using it. A good rule of thumb is to “wake” it up every week with a fresh feeding and some time at room temperature for the culture to work its way through its new food source, but I’ve brought back my culture after 4 dormant, chilly months before, so don’t sweat it if it lingers there for a few weeks. It will just take more feedings to get back to its normal, active level.

WAKING UP A DORMANT STARTER To wake up your starter after it's been stored in the fridge for a week or more, remove it from the fridge and allow it to come to room temperature. This can take anywhere from 1 hour to 4 hours, depending on the size of your starter.

Don’t be put off if the top has developed a grayish tint, if there’s a layer of liquid gathered on top of the culture, or if it smells particularly alcoholic; just mix it up and feed your starter as outlined in the section above. If it’s any other color, though, be wary. A stable sourdough starter will ward off bad bacteria, but if it’s been severely neglected, it could get infected with harmful organisms. This rarely happens. If it has an orange or pink hue or a fuzzy, moldy surface, throw it away. Keep refreshing your sourdough 2-3 times a day, until its back to its bubbly, tangy self. Rye is a magical, fearsome, and wholesome grain. Often grown as a cover crop, it's excellent at preventing field erosion over long winters and is relatively inexpensive for farmers. And rye is delicious for baking, especially when in naturally leavened breads.

Baking with rye is quite different than baking with wheat, especially in this 100% rye recipe, because of the grains' different chemical compositions. Rye still contains a type of gluten (a prolamin called secalin), but it can't create the same elastic bonds that wheat's gluten proteins (glutenins and gliadins) do. Instead, pentosans (a complex sugar present in rye that is also in wheat, but in lesser amounts) and starches are responsible for rye's crumb structure. When mixed with water, the pentosans in the rye swell and absorb large amounts of water, while its amalyse enzymes break down starches into sugar. But too much sugar and not enough starch will cause the rye bread's structure to collapse. Bakers refer to this as "starch attack." One way to slow down the enzyme activity and protect rye's crumb structure is to acidify the dough with sourdough starter. Another way is to use scalded, pre-gelatinized rye four as a portion of your dough. This recipe employs both techniques, and was developed for the Starrs Sourdough January 2020 sale. This is a 100% rye sourdough recipe with whole rye berries and sunflower, flax, and pumpkin seeds, using a rye sourdough starter. If you have a whole wheat or all-purpose wheat flour starter and don't want to make a new whole rye one, you can substitute in your own starter. The final dough won't be exactly 100% rye, but it'll be pretty close! The bakers percentages are listed alongside the ingredient weights, as well as for the total formula. RECIPE Yields one 1135-g loaf Levain 25g rye starter (20%) 125g whole rye flour (100%) 125g water (100%) Scald 125g whole rye flour (100%) 25g rye berries (20%) 25g sunflower seeds (20%) 25g flax seeds (20%) 25g pepitas (20%) 250g water (200%) Final mix 250g whole rye flour (100%) 125g water (50%) 10g salt (4%) (+ 475g scald and 275g levain) Total formula 500g whole rye flour (100%) 500g water (100%) 25g whole rye berries (5%) 25g sunflower seeds (5%) 25g pepitas (5%) 25g flax seeds (5%) 25g rye starter (5%) 10g salt (2%) EQUIPMENT Loaf pan Three bowls Mister or cast iron pan Plastic bowl scraper (helpful, but not required) Kitchen thermometer (helpful, but not required) PROCEDURE 1) Ensure your rye starter is active and bubbly by feeding it about 8 hours before you begin to mix your levain, and a day before you plan to begin your final mix. I usually feed my starter the morning of the day before I plan to bake. 2) 8-12 hours before your final mix, prepare your rye levain and scald. I usually do this the evening before I plan to bake.

3) The next morning, check your rye levain's activity level. When it seems to have reached its full expansion (about double its size when mixed the night before), combine the remaining mix ingredients.

4) Let ferment for 1 - 2 hours. 5) Line or spray a loaf pan and moisten or oil your hands. Then, scoop the dough into the tin and smooth the surface. This is where a plastic bowl scraper comes in handy. Sprinkle extra rye flour on the top of the loaf and place in a warm area. 6) Preheat oven to 500 degrees F. Ready your spray bottle/mister or place your cast iron pan at the bottom of the oven and boil more water about 30 minutes from your bake time. 7) Let bread proof for 1 - 2 hours. Rye doesn't rise anywhere near the same amount as wheat, or feel the same when poked. When the rye flour at the top develops cracks, it's a good indication that the bread is proofed. 8) Put the bread into the hot oven, and either mist with a spray bottle of water or pour boiling water into the cast iron pan at the bottom of the oven to create steam. Bake for 10 minutes at 500, then drop to 450 for 20 minutes, then 400 for about 30 more minutes. When the bread temperature is over 200 degrees F, remove from the oven to cool. 9) I recommend waiting at least 24 hours before cutting into this dense, nutty, aromatic loaf. Rye can be quite gummy if sliced earlier. It will last a week or more in your bread box or stored in a paper bag. |

|